Raccuglia and Son Funeral Home

If Caputo bread bags are one of the more recognizable items in Carroll Gardens, then Vincent Raccuglia is one of the more recognizable faces. He’s that handsome, older Italian gentleman who dons slacks and a fedora, tipping it to say “Hello, neighbor” when someone familiar rounds the corner.

The corner is Court and Sackett, and Vincent has been running it for years. When I blow in from the cold one morning, I ask him how he’s doing. Vincent kisses my hand and doesn’t hesitate. “Nice. Just like the way you look.”

I flashback to his father, Philip Raccuglia, in the late 80s, early 90s, sitting outside the funeral home, watching cars from a folding chair, wearing the same fedora, smoking his cigar, and biting down on it to give me a wink.

Charmers, those Raccuglia men. Like the flaws in your sidewalk, some things just remind you of home.

This home - the Raccuglia and Son Funeral Home - opened its doors in March of 1974. I always thought it was a family business that began with Philip but in actuality it was Vincent who started it all. A relative newcomer, unlike the faction of neighborhood funeral homes that had seen nearly two generations already passed down, Vincent’s concentrated curiosity in this particular line of work came from within. Philip Raccuglia was actually a longshoreman whose Red Hook pier happened to close up around the time Vincent began needing renovations done on the building.

“My father - he oversaw the top of this block,” Vincent says. “And you remember that!”

He likes that. I like that he likes that.

“If someone drove up and had to go to the medical center or something… it was ‘Leave the car here! We’ll watch your car.’ That was my father. His friends - his fellow longshoremen - they, too, were now out of work. They would see my father sitting off the corner and they’d say ‘Hey Philly! Whaddya doing?’ And my father would say, “Oh, my son…” and before you knew it - one guy was demolishing, one guy was plastering, one guy was painting. I had the longshoremen - skilled men - doing everything you see here for free. They did it for free, Sylvie!”

I think there may have been some rice balls from the foccaceria thrown in but even so. “It’s a beautiful thing,” I say.

“I was blessed,” he nods gravely, seemingly still caught in disbelief. “I’m telling you, baby, you can’t make this up.”

Before Vincent was met with the opportunity to acquire 323 Court Street, he spent the 60s learning everything he could about the business.

“Actually, I don’t like to say ‘business,’” he corrects us both. “Back then, it was an evolution of family service. You didn’t know an undertaker who just opened up a funeral home across the street from the dry cleaners store,” he says, dryly. “But it was in the early part of the 60s that I found something that meant a great deal to me - this profession and this life that it becomes,” Vincent says.

Choosing his words carefully, he continues. “In 1963, I got blessed. Got knocked out for a while. When I woke up, things were different in the neighborhood.” I have one eyebrow raised, waiting for him to elaborate. He knows I’m waiting, but still he says, “I got blessed. Things were different.”

Vincent then did what he could to gain the knowledge. He went to mortuary school, served an apprenticeship with Riverside Memorial Chapel (originally operated by a family - the Rosenthals), and took jobs at all the various funeral homes in our beloved Carroll Gardens/Cobble Hill neighborhood such as Scotto’s and Guido’s and Cusimano’s. He was dedicated to all of his jobs and stayed after hours just to keep learning. It wasn’t rare for Vincent to relieve somebody who had worked a long day. They could nap while he answered phones. He was a pallbearer, a driver, a funeral director, a cosmetician, an embalmer - jobs that were very relative to serving the people. But what Vincent had - and what he insists the Raccuglia family always had (“My mother’s a saint! My sister’s a nun!”) - was the human factor. Vincent points to his heart and says, “That comes from here.”

Vincent’s son, Philip, lives above the funeral home with his children and family. He is a licensed funeral director, undertaker, and mortician but most important, he possesses that human factor. “Go to any church in the neighborhood and they’ll tell you who was dressed in a little suit, walking down aisles and collecting, already building human relations,” Vincent beams.

A man from outside the parlor walks in. Vincent introduces him to me.

“This gentleman here? He’s a neighbor on the block. When there’s a funeral, he shows up at 5 o’clock, 6 o’clock in the morning. He comes to assist us. Very loyal. We have to get things done early around here. You can’t say ‘Vincent or Philip don’t feel too good, they got the sniffles, they’ll do it tomorrow’ - no, you can’t do that because there’s no margin for error. And then people know that when you show them the human factor, that some things can go to the right or to the left in the presentation and conduct of a funeral.”

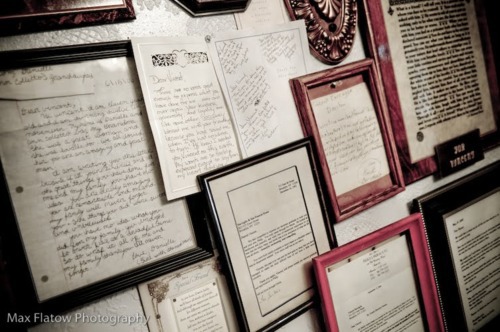

The walls are adorned - absolutely festooned - with bronze and copper plaques, framed photographs and letters - all expressing appreciation and gratitude for the Raccuglia’s tender manner with grieving families.

“Quite often, when I serve a family, I don’t let them go home when they’ve got a break between wake and burial. I say, ‘You stay here and my sister and my mother - we’ll make something for you.’ And we bring them rice balls and panelles from the focacceria.”

For Vincent (and myself!), this is what makes Carroll Gardens so special. Our area has certainly changed over the years, but we’re still a neighborhood that has evolved into that heritage of people who look out for each other.

And in the end, that’s what counts.

Here’s to tipping our hats and saying “Hello, neighbor.”